Introduction

Introduced to a mixed reception, the Nikon Df is the company’s answer to the plethora of models on the market with mechanical controls.

The design is derived from Nikons of yesteryear – though there’s no one model it closely resembles visually, other than perhaps a mix of the company’s first multimode 35mm SLR, the FA from 1983 and the N2020 (F-501) from 1986. Internally, the Nikon Df is a combination of the firm’s current digital models with the glass pentaprism and FX format 16-Mpix CMOS sensor borrowed from the flagship Nikon D4 and the 39-point AF system and shutter mechanism from the Nikon D610.

This both empowers and at the same time restricts the capabilities of the Df. On the one hand the sensor offers the same superb low light capabilities of the D4 with sensitivity running from ISO 50 to 204,800 (extended) but the shutter has only tops 1/4000th sec while the flash sync is just 1/200th sec.

Neither can the Df boast the same continuous burst rate of the D4 at 5.5 fps but has a viewfinder with close to 100-percent coverage and a large (0.7x magnification) image. To the rear it has a 3.2-inch (921k dot) high-resolution LCD panel for stills only. There’s no video capture option despite a fairly hefty $2749 ticket.

Like the earlier cameras from the 70s and early 80s, the Df is available in black and chrome finishes. It’s the smallest and lightest full-frame model in the firm’s line up, measuring 5.6 x 4.3 x 2.6″ (143.5 x 110 x 66.5 mm) and weighing 1.56 lb (710g)

Our labs have carefully analyzed the optical quality of over 90 models on the Nikon Df, including models such the ultra-wide DX format Sigma 8-16mm (12-24mm equivalent) f4.5-5.6 DC HSM and Nikon AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm f2.8G ED through to the highly acclaimed Art series 35mm f1.4 DG HSM from Sigma and the AF-S Nikkor 85mm f1.4, and the super-telephoto models such as the AF-S Nikkor 200mm f2.0G ED VR II and 400mm f2.8G ED VR.

New models added recently to the database include the new high-speed Otus Distagon T* 1,4/55 and Apo Sonnar T* 2.135 ZF.2 from Zeiss and the Nikon AF-S Nikkor 58mm f1.4G. We’ve also added the data from the full-frame AF-S Nikkor 24-85mm f3.5-4.5G ED VR as well as the 50-500mm f4.5-6.3 APO DG OS HSM, and recently re-vamped 120-300mm f2.8 EX DG OS HSM from Sigma.

Although the Nikon Df and D4 are quite diverse in the range of their abilities and aimed at different markets, the fact the Nikon Df shares a related sensor that’s highly regarded for its low light capabilities is a real highlight for potential users.

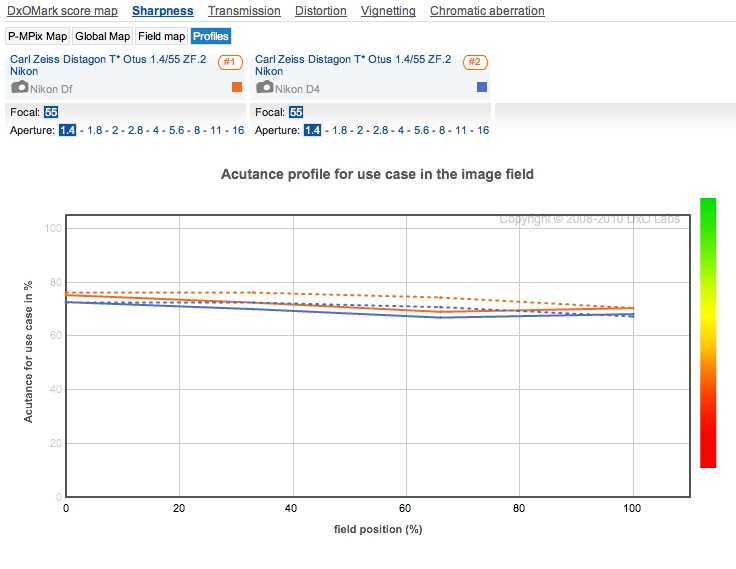

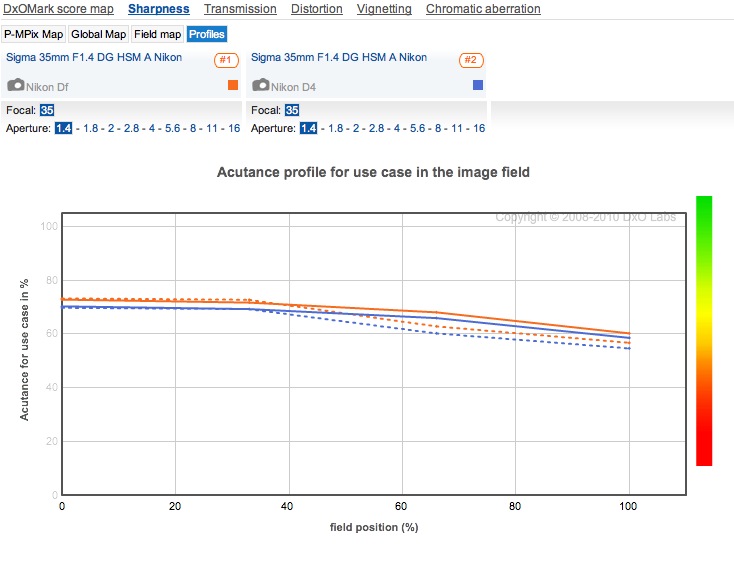

We were curious to see if Nikon had altered the OLPF (AA filter). By comparing the sharpness results between the two models with the best performing lenses in our database, it appears that the Df has a weaker AA filter. The Df sensor is capable of a slight but quantifiable increase in sharpness over the D4 when using the same lens, though by how much depends on the performance of the optics.

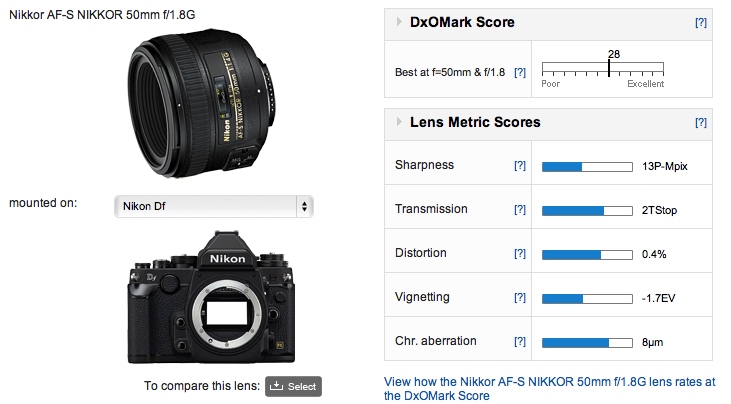

Launched alongside the Nikon Df was a new lens to match the retro looking camera. Optically it’s the same as the firm’s existing AF-S Nikkor 50mm f1.8G but it has a few cosmetic enhancements, including a chromed ring to aid mounting, like the earlier manual focus lenses from 70s and 80s. As the company claims the lens has the same optical construction, we only tested the standard model on the Nikon Df to see how it performs.

Given the price, just $220 (and about $50 less than the Special Edition) and with a DxOMark score of 28 and a 13P-Mpix sharpness rating, the standard AF-S Nikkor 50mm f1.8G is a good performer.

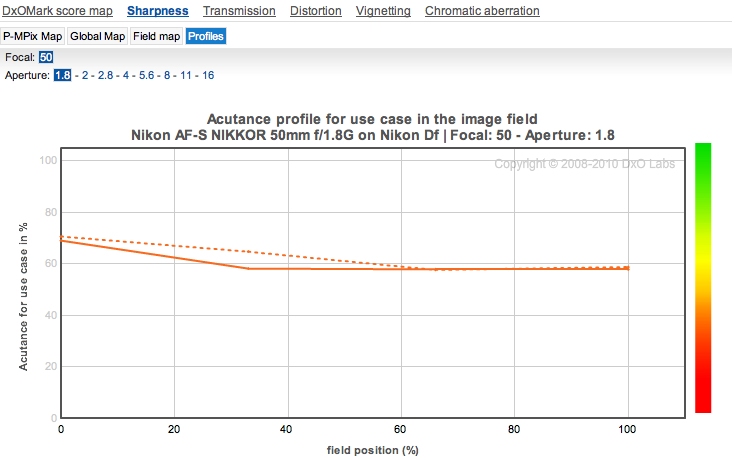

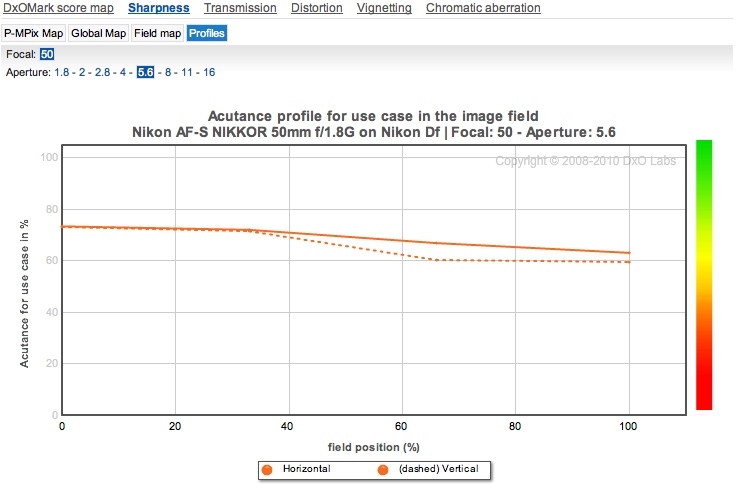

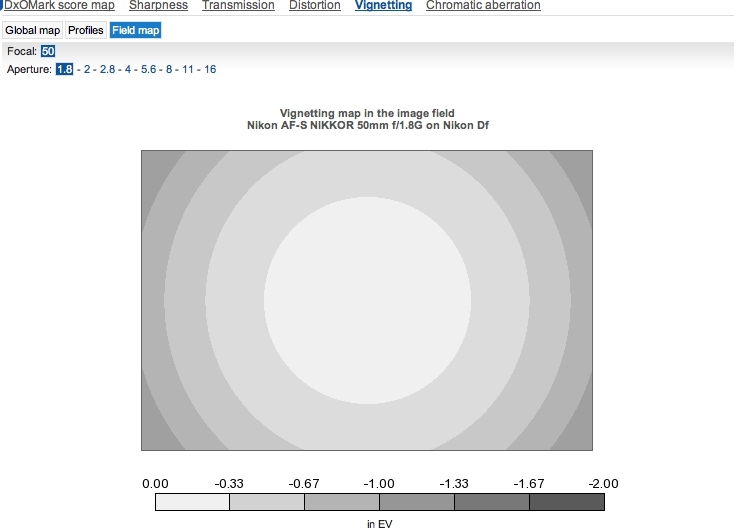

Wide open the lens has very good central sharpness but the edges don’t start to improve till stopped down to f2.8. However, if you want the corners to match the center you’ll have to stop down to f11.

The downside is that sharpness has started to decline from the optimum f4-5.6 aperture range. Unlike previous versions this lens has an aspherical element and it appears to help keep chromatic aberration to reasonably low levels. Some slight barrel distortion is evident and vignetting is noticeable at the initial aperture but it’s gone by f4. At 2TStops, even the transmission is impressive.

While any lens can take advantage of the low-light capabilities of the Nikon Df, high speed models are ideally suited to sensors like this. We were intrigued to see how two relatively new high-speed standard models would perform. The Zeiss Distagon T* Otus 1,5/55 (55mm f1.4) is the first in a series of ultra high-grade manual focus models and it has the best optical quality of all the lenses we have in our database. At $4,000, however, you would expect extreme performance.

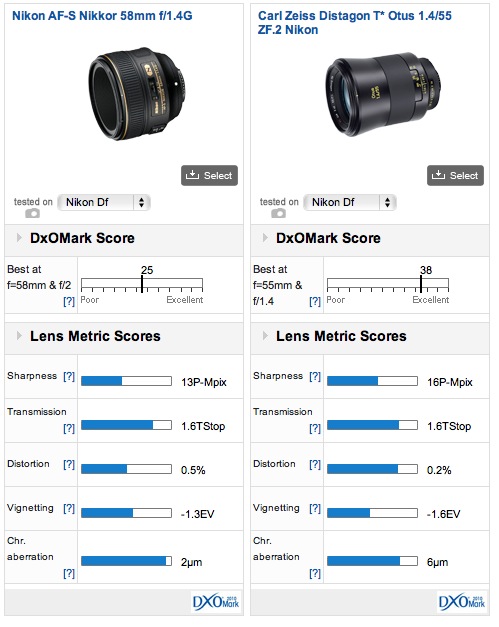

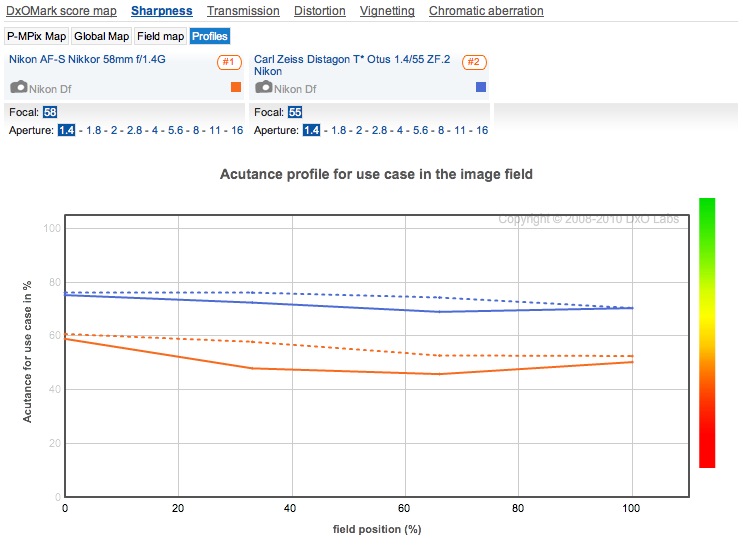

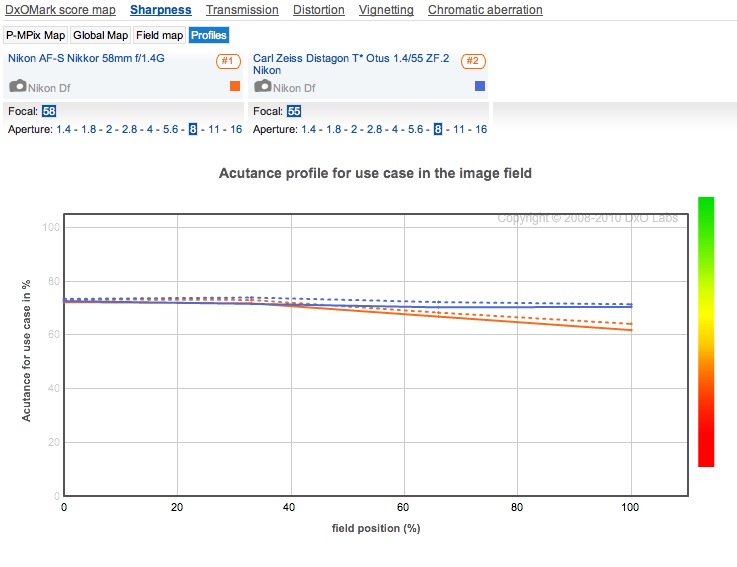

The Otus shipped just after Nikon launched their high-end model, the AF-S Nikkor 58mm f1.4G. At $1,700 and weighing less than half that of the Otus (13.6 oz (385g), this autofocus lens is Nikon’s premium high-speed standard.

Compared to the Otus though, it’s not optimized for sharpness at wide-apertures and it can’t match either the peak sharpness or uniformity of the Zeiss. While that doesn’t sound good, to be fair, it has an attractive drawing style wide open and it has very low levels of lateral chromatic aberration. It also has noticeable barrel distortion, which is unusual in a lens like this but it has less distracting vignetting than the Otus.

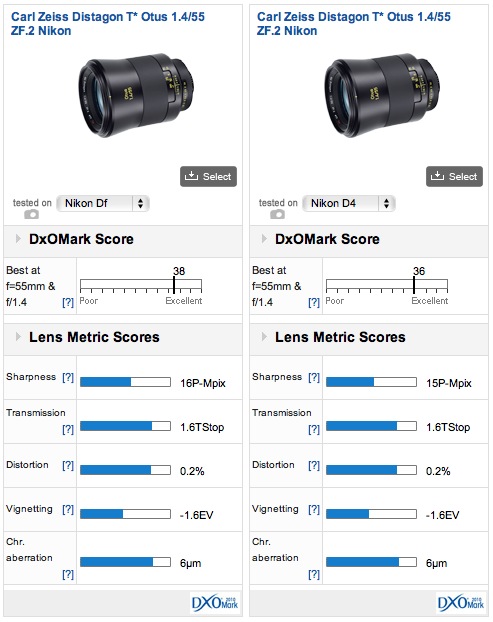

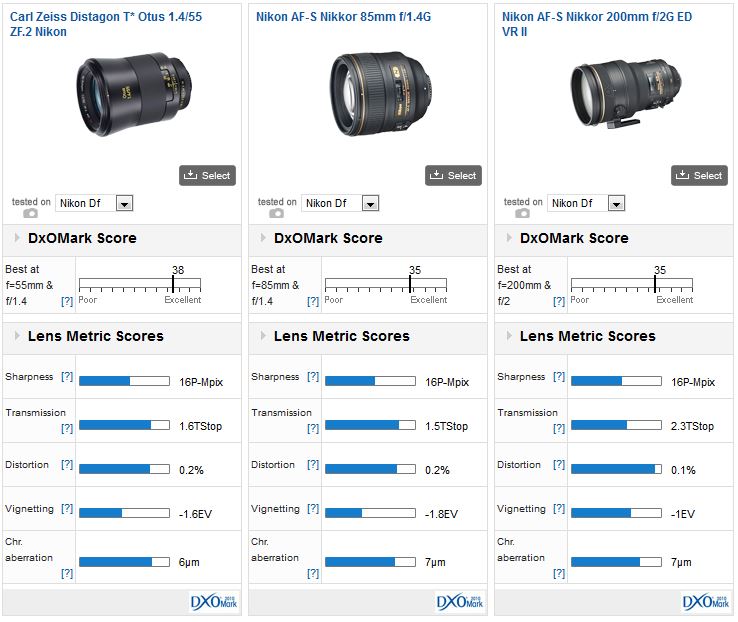

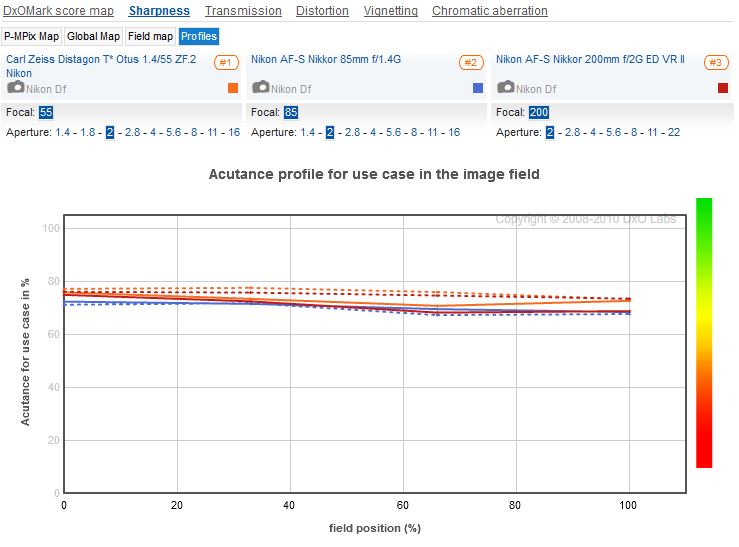

As with other cameras before it, the best performing lens on the Nikon Df is the $4,000 manual-focus only Zeiss Distagon T* Otus 1,4/55 (55mm f1.4) ZF.2. With a DxOMark score of 38 points, it continues to be the best-corrected lens we’ve seen (nothing else has really come close). And, it’s not surprising to see the perceptual sharpness rating (measured in P-Mpix) achieve the maximum theoretical figure indicating that the lens out-resolves the sensor (at least at peak sharpness). The same applies to other models as well.

Three lenses vie for second place and the Nikon AF-S Nikkor 85mm f1.4G, 200mm f2G ED VR II, and Zeiss Sonnar 2/135 all out resolve the Nikon Df sensor at their optimum aperture.

Similarly, the AF-S 300mm f2.8 and 400mm f2.8G ED VR also match the 16P-Mpix rating and deliver high uniformity even at the initial aperture. But it’s all very well selecting the most expensive lenses, you expect these to have good optical quality. In truth all of those lenses listed above perform very well indeed. If on a restricted budget, the Nikon AF-S Nikkor, 28mm f1.8G, 50mm f1.8G and 85mm f1.8G can all be recommended and may be all you need for general-purpose use.

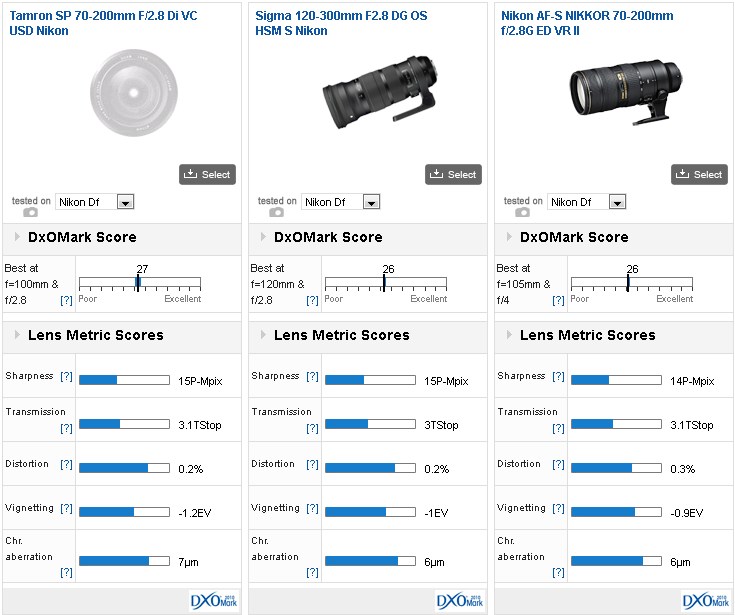

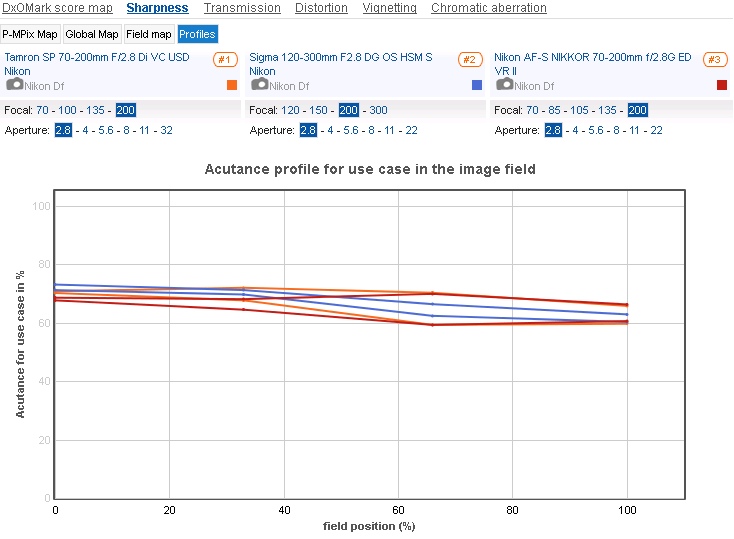

While it’s exceedingly rare to beat prime lenses for quality (we’re thinking of the AF-S Nikkor 14-24mm f2.8G ED), you can’t beat zooms for their flexibility. The best performing zoom on the Nikon Df is the relatively new stabilized Tamron SP 70-200mm f2.8 Di VC USD. At $1,699 it considerably cheaper than the Nikkor version, in third place at $2,699, though in real world terms the performance between the two is slight. We can’t comment on long-term durability or handling but based on optical quality alone the Tamron won’t disappoint. Peak sharpness is 15P-Mpix on the Df and an excellent performance for an ultra high-speed telephoto zoom.

Another third party made lens occupies second place, only this time it’s a Sigma, and a unique model at that. It’s the revamped 120-300mm f2.8 DG OS HSM S, a high-end zoom aimed at sports and action photographers to mitigate switching between 70-200mm and 300mm lenses at crucial times. At $3,600 it’s not for everyone but it’s much more versatile than a 300mm f2.8 and around $2,300 less than the Nikon offering alone. At maximum aperture it’s a very good performer throughout the zoom range, centrally at least.

If you have a new Nikon Df and a favorite lens, we would very much like to hear from you. Please leave a comment below, stating what lens it is and why you like it.

DXOMARK encourages its readers to share comments on the articles. To read or post comments, Disqus cookies are required. Change your Cookies Preferences and read more about our Comment Policy.